Sweet Vigilantes, your Vigilante Work Study dollars have been hard at work helping students who want to earn school fees, money for textbooks, etc. Using work study dollars I bought some of Ivan’s paintings and Ivan was able to pay the balance of his school fees and those of his sister, Lillian, for the term that has just ended. Now that you’re buying up the rest of his paintings, almost as fast as he can paint them, he and Lillian are in good shape for next term.

Opiyo Chris, the first Work Study scholarship kid, is teaching math classes to primary kids during their upcoming holiday break. He will earn enough Vigilante Kindness Work Study dollars to pay for everything he needs for his next term, while we wait interminably for his passport to be approved so he can finish his high school career in Medford, OR. where he received a full ride scholarship to a private high school.

And of course there’s Denis. I used Vigilante Kindness Work Study dollars to pay for textbooks and in return Denis is teaching the women of Te Okot to make paper bead jewelry, which will allow them to make and sell goods and earn money of their own. I love these business minded women so much.

My son, William, is also one of the recipients of the Work Study Vigilante Kindness dollars, but not in the way you might think. William works as a biology and computer lab assistant at a high school here. He is in college and uses the money he earns to pay his tuition, but also to pay the school fees of his younger cousins. William is such a hard-working kid, but this year he didn’t make quite enough to support his cousins as well, so your Vigilante dollars helped William pass on the gift of education to the next generation of his family.

There’s one last recipient of your Vigilante Kindness Work Study dollars. And he’s not a student. Patrick is a father of four and his two youngest children are in high school. I met his two youngest kids, Emmanuel and Lydia, on my first trip to Uganda when they wrote beautiful pieces for our book. Patrick is a part-time literature professor and has been struggling to pay their school fees on his shoestring of a salary. Teacher friends, I know you can relate. Because he’s an educated man and a teacher, I knew Patrick would be the perfect person to teach me Acoli. So each day I go to his house for an hour to an hour and a half and he patiently teaches me to speak, write and read Acoli. In return I pay him so that he can pay for Lydia and Emmanuel to attend school.

There are a few other things you should know about Patrick. He takes in his nieces and nephews who don’t have anyone to care for them. One of his nephews is my son, Martin, who Patrick rescued from the streets when Martin was a very young child. Another interesting fact about Patrick is that his father was a chief, but when his father became a Christian, he renounced his chiefdom because being chief meant preserving practices he no longer agreed with, like witchcraft and polygamy. So Patrick’s family doesn’t receive any of the benefits of being in the lineage of the chief because they have chosen to live as Christians, even though that means missing out on many privileges.

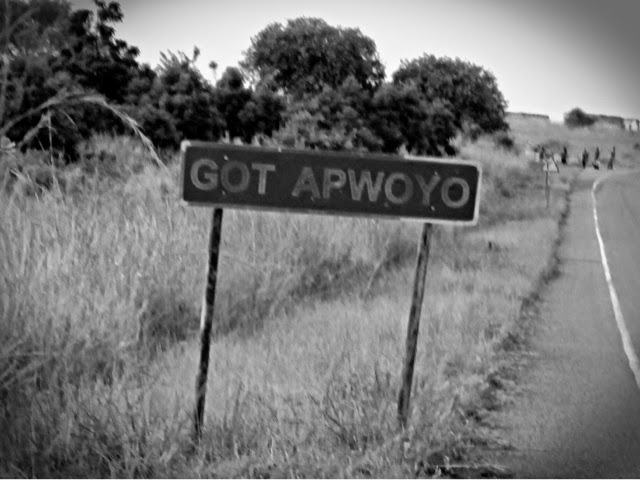

Needless to say, I’ve learned quite a lot from Patrick, but for our purposes I’ll stick to some things I’ve learned specifically about the Acoli language. The Acoli language doesn’t have the letters h, q, s, x or z. They also have a letter that makes the “ng” sound that looks like an n with a tail. My keyboard won’t type it.

Learning and conjugating verbs is the toughest thing for me so far. Pwonyo, one of my favorite verbs, means to teach. Leko means to dream. Ngwech means to ride a bicycle. And perhaps the hardest one of all for me, both to say and learn to do, is ling mot, meaning to be quiet and still.

In addition to learning verbs and the alphabet, I can now name body parts. The funniest one I’ve learned so far is “dog” meaning mouth. My mouth often gets me in trouble so I like the idea of being able to call it bad dog. Dog arach means “My mouth is bad.” It figures that would be one of the first sentences I’d learn.

Perhaps the greatest thing I’ve learned is that when the Acoli people speak of their feelings, they don’t speak of the heart, they speak of the liver.

Sweet Vigilantes of Kindness, it’s because of you that Ivan, Lillian, Opiyo Chris, Denis, Lydia, Emmanuel, and William’s young cousins get the privilege of being educated.

It’s with all sincerity and profound gratitude that I say to you, “Amari i wi cwinya.” I love you from the bottom of my liver.