If you’re newer to Vigilante Kindness, I’m glad you’re here, but you may want to go back and read a few posts before you read this one. Vigilantes who have been around a while, hold onto your hats, we’re going back to Bungatira.

Nothing is ever really lost, or can be lost,

No birth, identity, form–no object of the world.

Nor life, nor force, nor any visible thing;

Appearance must not foil, nor shifted sphere confuse thy brain.

Ample are time and space–ample the fields of Nature.

The body, sluggish, aged, cold–the embers left from earlier fires,

The light in the eye grown dim, shall duly flame again;

The sun now low in the west rises for mornings and for noons continual;

To frozen clods ever the spring’s invisible law returns,

With grass and flowers and summer fruits and corn.

-Walt Whitman

I love that poem, the idea that nothing is ever really lost. Walt Whitman had it right when he said time and space are ample. No amount of time or space can separate us from our loved ones. I’d like to add that no effort is ever in vain, no plan is ever for naught.

The part that’s resonating with me particularly today is the line about Spring’s invisible law returning. Spring comes in all her authority and seeds that have laid hidden in the soil through bare seasons, until the the right time and the right conditions collide, slip off their coats and from dark dormancy, green grows.

This is that kind of story.

Not long before I returned to Uganda, Denis messaged me that something very good had happened. I asked him to tell me what it was, but never heard from him about it again.

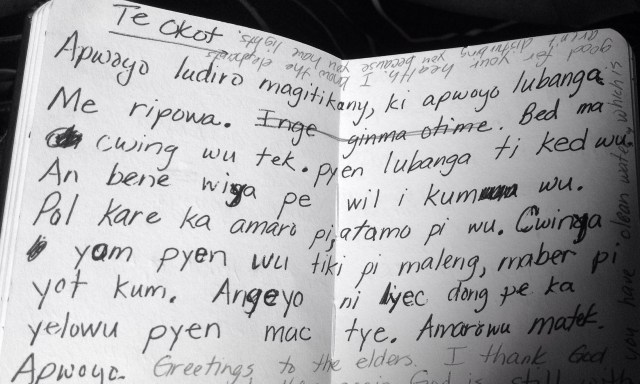

The night I arrived in Gulu, my mom, my sons, Denis and I had dinner together at a local pork joint. I sat wedged in between my oldest son, William, and Denis. William and Denis have become dear friends and they constantly tease each other. They tossed remarks back and forth over me, but during a rare cease fire, Denis leaned in and told me that his family was returning from Te Okot to live in Bungatira.

I nearly choked on my pork.

I fired about a thousand questions at Denis. What about the other chiefdom who poisoned your pigs? Where are they? How is it that you get to return? What does this mean for your land?

Over the din of the pork joint and the loud bunch I call my family, Denis unpacked the last year’s events.

There were ten chiefdoms living in Bungatira, two of which were the Pawel and the Aria. Denis’ family are Aria. It was select members of the Pawel chiefdom who poisoned Denis’ pigs, the same people who didn’t agree with the work of the Bungatira community group, the same people who claimed to be so disturbed by my presence.

I want to be clear about something, that it was not the Pawel group as a whole creating the trouble, only select members. Many Pawel lived and continue to live peacefully in Bungatira, and for that I’m incredibly grateful.

As it turns out, all of their anger wasn’t over the work the community group was doing, but was over land. I’ve said before that land is life here and it proved to be true again.

Those particular Pawel people wanted the land that Denis’ family was living on. It was fertile and near a stream, so they claimed it as their own, said that the land had belonged to them for many generations. The Pawel far outnumbered the Aria and so after meeting with their chief, Denis and his family moved to Te Okot, where they would be safe.

The people wanting Denis’ family’s land moved into their homes and took over their crops. To think of someone else forcing their way onto the land and living in Musee and Mama’s home turns my stomach to this day.

I thought that was the end of the story, but buried under conflict was a seed of justice just waiting to crack open.

Denis took their case and their history on the land, to the Aria lawyer, who brought it to the Pawel and Aria Chiefs. They heard the case and in a remarkable turn of events ruled in favor of Denis’ family.

Can you even believe it?

The select members of the Pawel tribe who’d killed Denis’ pigs, took their land and lived in their homes were forced by the Pawel chief to leave Bungatira indefinitely. They left and on my first weekend in Gulu, the Aria lawyer paid to transport Denis’ family, everyone from Musee down to my favorite kid, naughty Lucky Maurice, returned home to Bungatira.

Maybe you’re in a waiting period, a time when you can’t see the hand of God at work, a time when it seems like justice has been buried deep. Take heart, the invisible laws of Spring are at work and the seeds you’ve planted are waiting for the perfect moment to peel off their coats and grow anew.

For us at Vigilante Kindness, this means we now have two sites, in Te Okot and Bungatira, working together on the Paper Bead Project. For me, as Whitman says, the light in my eyes is now flaming again because now I have two places here filled with people I love. I’ll go visit my loved ones in Bungatira tomorrow and when I do, Whitman’s words will echo in my heart.

Nothing is ever lost.